THE BUMPING OF THE LOGS

Sitting in a park in Paris, France, watching the public interacting with the sound sculptures Iíve installed. Trying to decide if it was worth the effort. Trying to decide if Iíve chosen the right pieces to bring. ďLíart du jardinĒ, this event, is a paying entry salon that is mainly aimed at people buying arty things for their gardens, which of course doesnít mean art. My pieces are made to give people an artistic experience, visually and aurally, rather than to make them buy. Context is important. In a relatively commercial setting like this people often find it hard to pause and simply absorb. More likely they will glance and make some quick calculation about price (even though none are displayed) or whether they are in danger of being cheated aesthetically in some way. Or they will try and make some assessment of whether I am likely to sell anything.

This part of the park is wooded and pleasant to be in, away from the main crowd. One of my pieces Kissing Cousins is a mobile suspended three metres in the air consisting of nine slate slabs, which move with the aid of a small electric motor. I made it originally to be installed in the nave of a Romanesque church where it was surrounded by yellowish stone columns and a rich resonance. Here in the park it is green summer foliage that dominates, absorbing the slate sounds more than reflecting them. The contrast of sites is extreme and I start contemplating whether the sculpture survives this transition aesthetically, and also how the movements induced by the motor interact with those induced by the gentle breeze that is blowing. Its movements are slow and small, but if you pause even for a few seconds it is obvious what it does and you can easily hear the sounds it is making Ė scraping, percussive, clangsÖ A group of four or five thirty-somethings stride past me, chattering away. I think they are going to completely ignore my sculptures, I doubt if they have even noticed them, but as they pass under Kissing Cousins, the one on the left raises his rolled umbrella in the air and whacks one of the slates. It seems either it isnít moving enough or it isnít sounding enough for himÖ or perhaps itís just him, perhaps he has some sort of need to whack something. Heís not being aggressive; heís simply having fun. In any case he doesnít pause to look at or listen to the result of his umbrella whack, but moves on, still part of his chattery group.

Iíve almost finished setting up an exhibition of five sound sculptures in the music school at Chalon-sur-Saône. I realise that I havenít checked that all nine drips are working on my piece Rain Songs which I set up in a separate room because it requires a silent environment to hear properly. Iím surprised to find there is already a group of children kneeling on the floor close to it who are playing a set of stones that their teacher has brought with them. Two at a time, they are tapping the stones with small sticks. Their teacher encourages them to listen to the drips of water on the slate of the sculpture and to make their own sounds in relation to that. I observe in silence, entranced by their concentration and sure that itís the wrong moment to climb a stepladder and find out why one of the drips is not working.

What constitutes a musical experience? Maybe we need to look more at how sound is received rather than how it is produced. (Bearing in mind that the term music itself is shorthand for a large number of human activities that we find convenient to group togetherÖ) We can measure a sound, but we canít measure an individual personís experience of that sound. Each person will hear it differently. Physically, their sense of hearing will work differently, ranging from complete deafness to acute sensitivity to detail and nuance. Thatís a starting point. Their hearing will also be influenced by their other senses. But most of all, how and what they hear will depend on what their life has been, on what other experiences they have had until now. Every sound heard will make connections with memories of other sounds heard, with memories of dreams, with memories of mediated experiences through films, books, records, internetÖ and with fantasy and imagination, ideas about the future or wishes for how the world ought to be, but isnítÖ In a particular place at a particular time there are probabilities of how a sound will be experienced, but we can never get inside someone elseís head to hear exactly what and how they are hearing, or inside their body to know what physical sensations a sound induces. Music, if it is successful, allows and stimulates an individual to construct his or her own reality. It doesnít impose a reality, it enables. Then it allows growth, questioning and development, refinement and confirmation.

For years now I have been saying that my work is equally related to the traditions of music and sculpture, but because my background was more from music, if I had to choose which was more important I would say music. Now Iím not so sure. Sometimes I have found that my musicianly habit of being active, striving and eventually mastering an instrument - treating it as a tool for realising an imagined sound - can place a constraint on the resulting sound. More and more I find that the sculptures I have made have a strong character of their own and they respond better to sensitive exploration rather than colonisation and exploitation. Step back from them, donít push them around, give them space and time. This is not a new idea in western contemporary music of course, the principle was well established by John Cage and others and certain (not all) approaches to improvisation in the second half of the last century, but for me it seems to be taking a lifetime to learn it and absorb it and relearn it and find my own version of it. One of the reasons I like certain dancers working with my sculptures is that they donít try to make them into musical instruments or play music with them. They relate to them physically with their bodies, and this sometimes includes making sound, but the aim is not music. If you aim for music, that implies that you know what music is. I certainly donít know what music is, in fact Iíve never known what music isÖ but it has always stimulated me to wonder what it is. In my own categories, there is a big difference between a musical instrument and a sound sculpture. It is simply that a musical instrument requires a musician to play it and a sound sculpture doesnít. A sound sculpture may need to be activated by a human hand and it may respond to skilled manipulation, but it wonít need the refined rhythmic and melodic skills of a musician. There are, of course, objects that fall between the two or can work as both, but the distinction is important because it represents a different way of being.

In a plane tree in a museum courtyard in Mainz dancer Erick Jimenez

wriggles along a branch near my slowly rotating pieces of slate. His

movement is as slow as a sloth. His bare torso rubs against the bark

of the tree, sensing its form through his skin. The sculpture, Protecting

Leaves, intertwined with the tree, echoes its form without touching

it. Sculpture and dancer relate through the tree.

In the barn next to my house dancer Lisiane Michel and I walk in circles

round a square of eighteen slates laid flat on the ground. Thirty centimetres

above these, suspended by a wire from the ridge of the roof, is a slate

rock weighing perhaps twenty kilos. I stop walking and push the rock

towards Lisiane. She takes it and gently swings it back towards me.

The rock pulls a small lump of rubber across the slates making irregular

circular melodies, scraping and bouncing. We swing it in circles, sometimes

catching it in our arms, sometimes dodging out of its path. Gravity.

Gravité.

So is it useful to describe what I do as music? Ultimately, what I am

discussing is how an individual relates to the world, how he or she

explores the world, how they create their own world and how they make

some sort of statement in the world, and finally how they change the

world (in whatever small way). If we look at it like that it really

doesnít seem right to call it music or sculpture or dance or whatever.

More than that, it might hide what it actually is to give it a name.

This summer after a concert at a jazz festival in Coutances by the trio

Slate, someone came up and said that in the performance was the whole

of life, ďIl y avait toute la vie dedansĒ. I was touched because it

was a sincere compliment but also because I think it gets nearer to

what I am trying to do than the categories of art and music. The whole

of life though is an exaggeration. Itís just life, but itís life with

a certain slant.

I am trying to encourage people to look and listen in a certain way. For many years, mainly between 1984 and 1998, in British schools I led workshops where children made their own instruments, and then made music with them. It was exciting and often anarchic. Most of the children loved making things but sometimes were frustrated that they couldnít achieve something as refined as the instruments they knew. The challenge of my role in these situations was to make them appreciate the value of what they had done. Use the instrument, even if it isnít perfect, and make sounds with it. I would devise structures for composing music in groups, simple sequences of who plays when, or treating improvisations as conversations, or instructions as to whether to play fast or slow, loud or quiet. Often it was really difficult to get the whole group concentrating together and genuinely being a group. A useful tool in this was recording. First, it was easy for the children to understand that recording was an event and needed group concentration. Then on playback, the groups were often surprised how good there music sounded. What had seemed to them like a difficult mess when they were doing it turned out to be worth listening to, to have a character of its own. So even if some of the instruments they had made fell apart as soon as the tape stopped rolling, there was some evidence of what theyíd done and in some way (small or not so small?) their ways of listening had been challenged and developed.

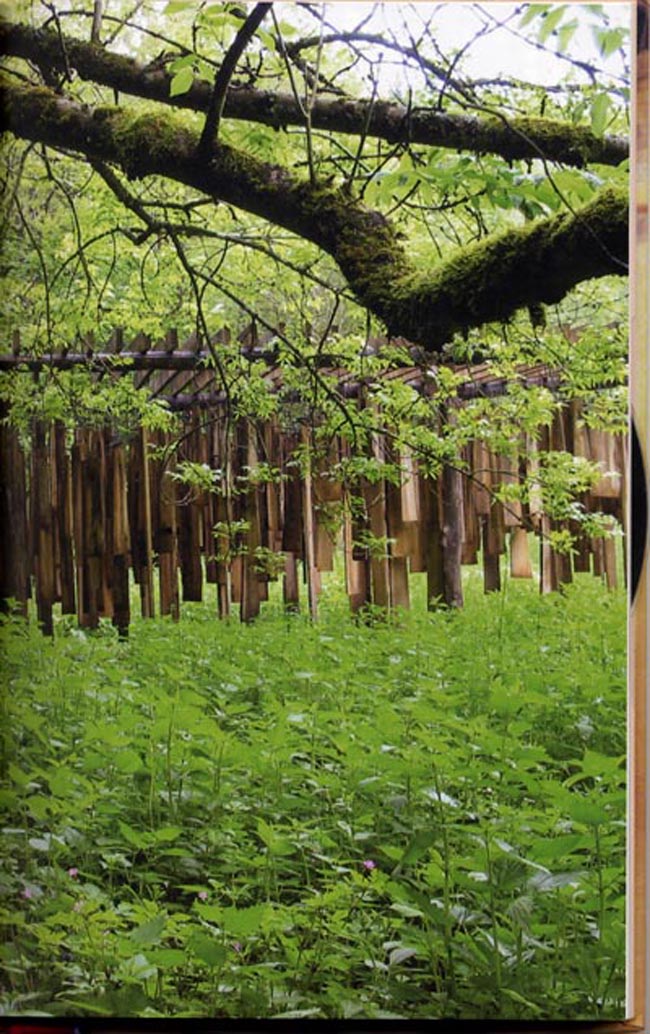

In a forest in Luxembourg, near the village of Hoscheid, you can take

a two-hour walk round a sound trail which includes five of my sound

sculptures. The village itself is at the top of a hill and the first

sculpture, Facing Out is designed to sway in the wind and make

oak keys clack against each other. Maybe as you descend into the forest

youíll hear a skylark singing high in the sky and youíll be able to

play a duet with it on the Skylark Marimba. Down in the valley,

youíll notice the trickling or gushing sounds of the river, before you

find Choeur de la Forêt (Forest Choir) a mass of suspended

oak planks that you can walk into and play with or stand back from and

listen to the wind moving them. Whichever you do, the wood and water

sounds will merge together. As you climb the valley side again maybe

youíll hear or at least feel your own heart beating hard, and need to

pause to wipe the sweat off your face. Eventually youíll find Buried

Resonance, again made from hanging oak planks, but this time just

eight of them with resonating tubes buried in the bank behind them.

Each plank has a rubber beater that you can swing into it, its mechanical

form suggesting particular rhythms and melodies, the tubes amplifying

the deep bass of the woodís sound.

In the end though, the point of all this is not just participation but

listening and sensing.

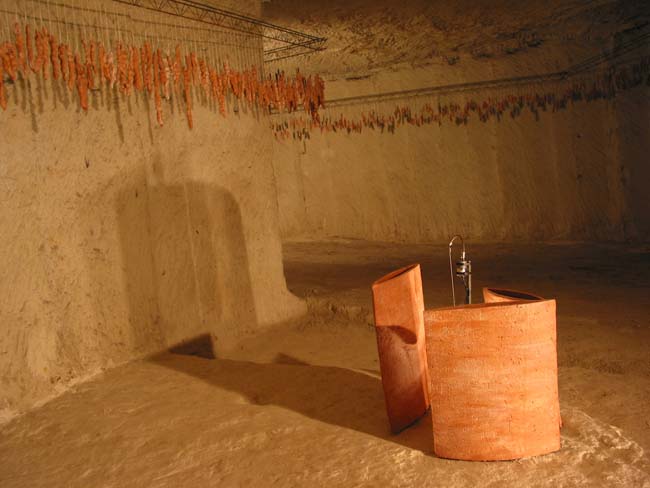

The Carrière de Vignemont at Loches, near Tours, is an underground

network of tunnels that was a stone quarry, then a mushroom farm and

now a tourist attraction. Inside until a few years ago you heard mainly

the sounds of footsteps and peopleís voices. Now at different points

you hear the gradually changing melodies of water dripping on to slates,

slabs of slate scraping together, whispering wood, air gurgling through

water into bamboo pipes, ceramic percussion... Your participation is

limited to changing your position in relation to each sculpture. As

you approach a sensor responds to your presence and the sculpture starts

moving and sounding. You see it differently because of what you hear,

you hear it differently because of what you see. You feel different

because you are under a mass of stone. The reverberation in the long

tunnels gives you an expanded awareness of volumeÖ.

Chance can help at different levels. The idea for my dripping sculpture

Rain Songs first came when I took some slate marimbas outside

to photograph. It started raining, but rather than rushing the marimbas

inside I rushed my tape recorder outside to capture the great sound

they were making. That was one sort of chance; another is the aleatoric

melodies made by the drips of the finished sculpture. Years later, a

third sort came into play when I was recording the sculpture together

with my soprano sax. A cow mooed in the field nearby. Whether she was

responding to the sax or simply hungry or something else, I donít know,

but for me her contribution made the duo into a trio and completed an

incomplete piece. Perhaps that wasnít chance.

So for me music and art are part of the natural world, not separate

from it. Sometimes sounds remind me of music unexpectedly. Outside the

Arnolfini gallery in Bristol one winter evening the wind was catching

the slots in the sides of some traffic bollards in such a way as to

produce flute like overtone melodies. A magical moment that Iíll never

forget. On each side of the bed where I sleep with my partner is a small

quartz alarm clock. The alarm sound doesnít interest me, but the ticking

does. I noticed it first when the tick of one clock came exactly in

the gap of the other, making a symmetrical stereo. Then the following

night I noticed the phase had very slightly shifted to make a lopsided

lilt. And so, in a process slower than nearly all music, the sound is

developing over weeks and months. I donít notice it every night but

when I do I have a tiny moment of pleasureÖ

So to go

back to my original question about the Paris park, yes, of course finally

it was worth it because who knows what special moments the sculptures

provoked and in what direction peopleís lives moved afterwards. What

seems important is not just to make the work, and of course somehow

get paid for doing it, but over and above that to give it as a gift

in many different contexts with no strings attached and without the

baggage of ownership. And then allow oneself to receive the gift of

the attention of others. Thatís what I try to do.

Will Menter,

January 2006

First

published with the title "Sound Sculptures" in Unknown

Public no.17, 2006

next : journeying

traduction

de cette article

writing by will

home page